From an early age my parents instilled me with a very healthy disrespect for authority. Any rules or regulations I encountered where met with some degree of suspicion. If I was told not do something, I immediately wanted to try doing it.

The negotiation

I have my own children now, and I see in them a similar quality, assuming that it can be called a quality. If I say not to do something, they both instinctively recognises that if an action is ‘not allowed,’ it is of some interest and so the negotiating starts, always asking, ‘why can’t I do it?’

And although they are young, if I give them a reasonable answer, they will pay attention and oblige me with their agreement however if I don’t give them a good explanation, I will inevitably find one of them trying out the sometimes very dangerous, ‘not allowed,’ action all by themselves.

Children know instinctively that although sharp knives are dangerous, they can also be useful.

I didn’t have the courage to tell my career guidance teacher at school that I had planned to go to London and train as a dancer after my Leaving Cert. so, ‘I beat around the bush,’ telling him that I wanted to do something that was a bit special. For some reason he assumed that I wanted to be a priest and I was sent to talk to the chaplain. The chaplain wanted to take me on a religious retreat to deepen my connection with God and as you can imagine at this point, I started to panic and blurted out the truth, that I In fact wanted to become a dancer.

Children know instinctively that although sharp knives are dangerous, they can also be useful.

On the North side of Dublin in 1988, many people found it easy to tell me why wanting to be a professional dancer was an impossibility but none could convince me, their arguments did not have enough energy to influence my conviction.

My father never told me this when he was alive, as his generation were not practiced in expressing their feelings but when I told my father what I wanted to do with my life, he was worried about me. He was worried that I would be poor, that I would later regret my decision and that I would eventually have to return to university, complete my education and get a ‘proper job.’ He saw me as potentially wasting all my natural academic abilities in pursuit of a career that was unstable and only available to the very few and fortunate. But even my father whom I loved and feared, could not convince me to change my mind.

I auditioned for three schools in London and got accepted in two. Not because I was any good but because I was a young and a man and young men were seen as a type of investment, it meant that the fee-paying women could be guaranteed weekly pas de deux classes, an important part of the syllabus of any good ballet school. In the three years I spent at the Central School of Ballet in London, I got very accomplished at partnering and lifting women dancers high over my head.

I also auditioned at the London Contemporary Dance School where I was given a physical examination making me feel a little like a racehorse or a greyhound. I was told that I would never become a dancer because my knees would not last the three years of training much less a full career as a dancer (I am now nearly 52 and my knees although ageing are still working).

At the age of 18 or 19, I signed up to the Central School of Ballet with only a one-year foundation course in dancing to back me up having never trained as a dancer before this. I had played Rugby at school for 5 years and was muscle bound. I was uncoordinated in some ways, unmusical and anxious. I could not remember sequences of movements. I could not even tell my left from my right. To this day I still have to rub the middle finger of my right hand along the callous on the side of the index finger of the same hand, to know what is right and what is left.

At Dance School, I was soon told I would never be a ballet dancer, that I should think about auditioning for Cats the Musical. So, I went to see Cats the Musical but fell asleep just after the interval.

Because of an inspirational choreography teacher, I had at Dance School, I started choreographing in my first year and once I had the opportunity to show my first piece of work, at the age of 19, my path was set.

I have learned that many people will delight in telling you why you can’t do something, I was told I could not be a dancer, then I was told that I could not be a choreographer, then I was told I could not be a director. But where there is a no, there always has to be a why?

there always has to be a why

A no is like a line or a border. When I hear no, I sometimes ask why, and very often you find that when you peel away the superficial layers of the force behind the no, that you discover that the no is founded on some senseless, old prejudice or some meaningless desire to maintain some self-serving status quo.

If the ‘no,’ is based on the rules or foundation of an art form and those very foundations are showing clear signs that they need to be dug up and replaced then that ‘no,’ has absolutely no value, to me, at least.

I have learned that many people will delight in telling you why you can’t do something

One aspect of the mind that I feel is relevant here is the play between the conscious and the unconscious. The conscious mind likes form, it likes shape, lines and parameters, the unconscious works silently, formlessly, and in the dark. It is connected to a deeper intelligence and one of its main functions is to be your creative guide.

The conscious mind is useful when you are paying your phone bill or withdrawing money from the bank or changing the wheel of your car but it is less useful when you are making art. The unconscious cares little for borders or for the way things have always been done.

Looking back now I can see how my unconscious mind guided me delightfully and sometimes very painfully through the last thirty years of my life. And I can see now that whenever I have tried to use conscious or reasonable thought to make decisions relating to my art, it has never gone particularly well.

I am interested in the meaning of the word, aliveness as I spent years wondering what are the qualities that make one performer watchable and another less so. I have decided that it has something to do with the fact that when a performer thinks too much their head and their body separate energetically and when this fracture occurs, they become less alive. Even in a very coordinated physically impressive person, if they are thinking as they are moving, they won’t be nearly as watchable as another person whose consciousness is not concentrated in their head but spread through their entire being. A performer whose body and mind and breath are integrated will appear to be extremely watchable because in this state, they are most alive.

The unconscious cares little for borders or for the way things have always been done.

I will never forget the first time I saw a tiger in Dublin Zoo. I was only a child so you can imagine how enormous the tiger looked and although this animal was clearly sad about being confined to a small enclosure in the very extremities of North Western Europe, I will still never forget its beauty and how it moved and how being in its presence made me feel, imagining what it must be like to encounter one of these beasts in the wilds of the Bengali Jungle.

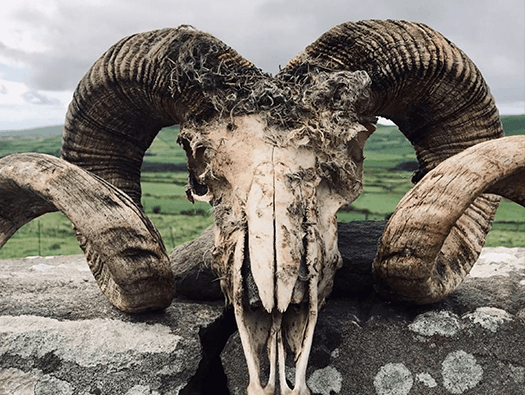

an extraordinary beast

Going to the theatre needs to be like this, like meeting a wild an extraordinary beast in the woods and then having an energetic conversation with them. We go to the theatre to hear, see and feel things we cannot hear or see or experience anywhere else. This is getting increasingly challenging to achieve because of the unfathomable advances in media and technology. On the internet you can witness anything you want whenever you want. If you would like to witness a man being beheaded, just click.

You are one click away from just about seeing anything. But there is one thing you can’t access on line and that is a deep energetic connection with another breathing, sensing, energetic being, be it animal or human. This can only happen in the company of another living beings in real space and in real time. And this is the realm of the theatre.

I am in this game for one reason and one reason only, so I can be present when these sorts of encounters unfold. To see the energy created amongst a group of performers move from the stage and envelop the audience. To see that same energy travel back towards the stage propelled by the intensification of the audience’s watching and listening. And then to see it magnify further and be sent back into the auditorium again. To watch as a game of energetic ping-pong unfolds until it climaxes as the performance ends.

It has taken me thirty years to begin to understand the energetic dynamics of performance in the theatre and I wholeheartedly believe in its holistic and restorative power. To cultivate the power to make this kind of work one needs to develop certain qualities. One needs to became a master of the art of making connections. To achieve this, you first need to know yourself, inside and out. Every nook and cranny needs to be explored. Anything you have not processed will seek to be processed, and this can be most uncomfortable experience, especially if it happens without warning, in front of two thousand people in a live performance.

Most importantly you need to learn to relax and this is only possible when one becomes familiar with and in acceptance of the ever-changing nature of being.

When something needs to happen, let it happen. If something needs to occur it will occur.

I approach my projects like this now. If a dance / theatre work needs to come into existence, it will. And nothing will stop it. I love it when you begin to notice on certain projects that it is no longer about making it happen but instead it becomes about giving in and watching the creation come into existence whether you like it or not.

When something needs to happen, let it happen. If something needs to occur it will occur.

When things go wrong it’s never much fun but the pain can be assuaged a little by the knowledge earned through experience that when things go awry it’s one of the finest times to learn and to accept some previous indigestible truth about what it is you are doing or what it is you need to change.

I can’t think of a better place to develop as a human being than by working in the theatre.

I never sought to be ‘international’ and although I take great pride in the moments when the company has toured to London, New York, Paris or Sydney and plays in all sorts of prestigious venues and festivals, I don’t take much pleasure from sitting on airplanes or waking in hotel rooms not knowing where I am. But the international element to what we do was something I could not avoid. It was simply always going to happen so I just let it happen and have learned to adjust my behaviour around it.

The practical advantages of having your work tour outside of Ireland are significant but mostly because they allow you to diversify your base and source of potential financial and energetic support. Without International support you can become very vulnerable to the whims and political dynamics of one funding body.

The fact that our company has always being populated by international artists is not premeditated or the result of some policy decision that was taken at a board meeting. The show needs a cast and the show will demand who that cast will be. On Swan Lake, for example the dancer who plays Jimmy (our Prince) lives in Auckland, the dancer who plays his mother lives near Canberra but the show demanded that these two artists would be part of it and so they are part of it.

the master shapeshifter

I have also learned to never plan beyond the premiere. That planning is contrary to any serious act of creativity. Yes, it is expensive and energy consuming for the artists living in the Southern Hemisphere to come and perform in Moscow and then in Cologne and then in Clonmel but either it will happen or it will not happen and I am delighted to accept whatever outcome unfolds.

If I can’t give the show what the show demands, then I won’t make the show. Now I accept that this can sound a little irresponsible but it is quite the contrary. I do everything that needs to be done to ensure the show can manifest in its finest expression but after this we must allow things to unfold naturally and get busy about keeping out of the way. To have the strength and conviction to accept things as they are meant to be. To not get caught in the memory of some bad experience and neither to allow our expectations or desires of what we would like to happen obscure our clear seeing.

A great artist in my view is a master shapeshifter, a person who can cross borders, either silently, secretly or with a sledge hammer and dynamite if necessary. It’s a person who has the strength to take responsibility for their actions and who is comfortable to sit with the related discomfort when necessary and through it all keep the light in their eyes shining.

Michael Keegan Dolan, 2017